Programmer’s manual¶

Build system¶

Yade uses cmake the cross-platform, open-source build system for managing the build process. It takes care of configuration, compilation and installation. CMake is used to control the software compilation process using simple platform and compiler independent configuration files. CMake generates native makefiles and workspaces that can be used in the compiler environment of your choice.

Building¶

The structure of Yade source tree is presented below.

We shall call each top-level component module (excluding, doc,

examples and scripts which don’t participate in the build process).

Some subdirectories of modules are skipped for brevity, see README.rst files therein for more information:

cMake/ ## cmake files used to detect compilation requirements

core/ ## core simulation building blocks

data/ ## data files used by yade, packaged separately

doc/ ## this documentation

examples/ ## examples directory

gui/ ## user interfaces

qt5/ ## same, but for qt5

lib/ ## support libraries, not specific to simulations

preprocessing/ ## files associated with creation or generation of the simulation

dem/ ## creating a DEM simulation

potential/ ## creating a PotentialBlocks or PotentialParticles simulation

README.rst ## more information about this directory

pkg/ ## simulation-specific files

common/ ## generally useful classes

dem/ ## classes for Discrete Element Method

README.rst ## more information about this directory

postprocessing/ ## files associated with extracting results for postprocessing

dem/ ## general data extraction from DEM, no particular data target

image/ ## creating images from simulation

vtk/ ## extracting data for VTK

README.rst ## more information about this directory

py/ ## python modules

scripts/ ## helper scripts including packaging and checks-and-tests

Header installation¶

CMAKE uses the original source layout and it is advised to use #include <module/Class.hpp>

style of inclusion rather than #include "Class.hpp" even if you are in the same directory.

The following table gives a few examples:

Original header location |

Included as |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Automatic compilation¶

In the pkg/ directory, situation is different. In order to maximally ease

addition of modules to yade, all *.cpp files are automatically scanned recursively by

CMAKE and considered for compilation.

To enable/disable some component use the cmake flags ENABLE_FEATURE, which are listed in:

When some component is enabled an extra #define flag YADE_FEATURE is passed from cmake to the compiler.

Then inside the code both the .cpp and .hpp files which contain the FEATURE feature

should have an #ifdef YADE_FEATURE guard at the beginning.

Linking¶

The order in which modules might depend on each other is given as follows:

module |

resulting shared library |

dependencies |

|---|---|---|

lib |

|

can depend on external libraries, may not depend on any other part of Yade. |

core |

|

|

pkg |

|

|

gui |

|

|

py |

(many files) |

|

Development tools¶

Integrated Development Environment and other tools¶

A frequently used IDE is Kdevelop. We recommend using this software for navigating in the sources, compiling and debugging. Other useful tools for debugging and profiling are Valgrind and KCachegrind. A series of wiki pages is dedicated to these tools in the development section of the wiki.

Yade is agnostic to the IDE used; it can be compiled and run directly from the command line. You can modify the source code using any text editor, such as vim https://www.vim.org/, emacs https://www.gnu.org/software/emacs/, vscode https://code.visualstudio.com/, or any other editor of your choice.

Hosting and versioning¶

The Yade project is kindly hosted at GitLab:

The versioning software used is GIT, for which a short tutorial can be found in Yade on GitLab. GIT is a distributed revision control system. It is available packaged for all major linux distributions.

The repository can be http-browsed.

Development process¶

Git is used for version control. The main development branch is called master and is hosted at GitLab.

For the development process, the following steps are recommended:

Clone the repository to your local machine:

git clone https://gitlab.com/yade-dev/trunk.gitCreate a new branch for your work:

git checkout -b my-new-featureMake your changes and commit them:

git commit -am 'Add some feature'Push to the branch:

git push origin my-new-featureSubmit a merge request on GitLab: Merge Request

The merge request will be reviewed by the developers and, if accepted, merged into the main branch. Yade has a wide range of pipelines that are automatically triggered by GitLab when a new commit is pushed to the repository. These pipelines include building the software, running tests, and generating the documentation. The results of these pipelines can be viewed on the GitLab CI/CD page or by clicking on the green checkmark next to a commit in the GitLab interface. If some tests fail, the developers will be notified and the merge request will not be accepted until the issues are resolved.

It is required to add at least one line into the ChangeLog file in the root directory of the repository for each merge request. This file is used to generate the release notes for each new version of Yade.

How to make a release¶

The release process is automated using GitLab CI/CD pipelines. The release process is triggered by creating a new tag in the repository.

The tag should be named according to the semver convention, (e.g., 2025.2.0), whre the first number is the

year, the second number is the month, and the third number is the patch version.

The release process will build the software, run tests, and generate the documentation.

Create RELEASE file in the root folder with the version number in it.

Update Changelog file, put the proper date and version number in the top of the file.

Create branch using the following command and format:

git checkout -b YYYY.M.0

Tag release “git tag -as YYYY.M.0 -m”YYYY.M.0”

Return to master branch and remove RELEASE file

Push master, new branch and tags to gitlab

Download tar.gz

Create asc-file (signature):

gpg --armor --sign --detach-sig tarball.tar.gz

RELEASE file should contain the version number in the following format:

YYYY.MM.0

where YYYY is the year and MM is the month of the release. For example, the release file for the February 2025 release should contain the following text:

2025.2.0

Build robot¶

A build robot hosted at UMS Gricad is tracking source code changes via gitlab pipeline mechanism. Each time a change in the source code is committed to the main development branch via GIT, or a Merge Request (MR) is submitted the “buildbot” downloads and compiles the new version, and then starts a series of tests.

If a compilation error has been introduced, it will be notified to the yade-dev mailing list and to the committer, thus helping to fix problems quickly. If the compilation is successful, the buildbot starts unit regression tests and “check tests” (see below) and report the results. If all tests are passed, a new version of the documentation is generated and uploaded to the website in html and pdf formats. As a consequence, those two links always point to the documentation (the one you are reading now) of the last successful build, and the delay between commits and documentation updates are very short (minutes). The buildbot activity and logs can be browsed online.

The output of each particular build is directly accessible by clicking the green “Passed” button, and then clicking “Browse” in the “Job Artifacts” on the right.

Debugging¶

For yade debugging two tools are available:

Use the debug build so that the stack trace provides complete information about potential crash. This can be achieved in two ways:

Compiling yade with cmake option

-DDEBUG=ON,Installing

yade-dbgsymdebian/ubuntu package (this option will be available after this task is completed).

Use Logging framework described below.

These tools can be used in conjunction with other software. A detailed discussion of these is on yade wiki. These tools include: kdevelop, valgrind, alleyoop, kcachegrind, ddd, gdb, kompare, kdiff3, meld.

Note

On some linux systems stack trace will not be shown and a message ptrace: Operation not permitted will appear instead. To enable stack trace issue command: sudo echo 0 > /proc/sys/kernel/yama/ptrace_scope. To disable stack trace issue command sudo echo 1 > /proc/sys/kernel/yama/ptrace_scope.

Hint

When debugging make sure there is enough free space in /tmp.

Logging¶

Yade uses boost::log library for flexible logging levels and per-class debugging.

See also description of log module.

A cmake compilation option -DENABLE_LOGGER=ON must be supplied during compilation [1].

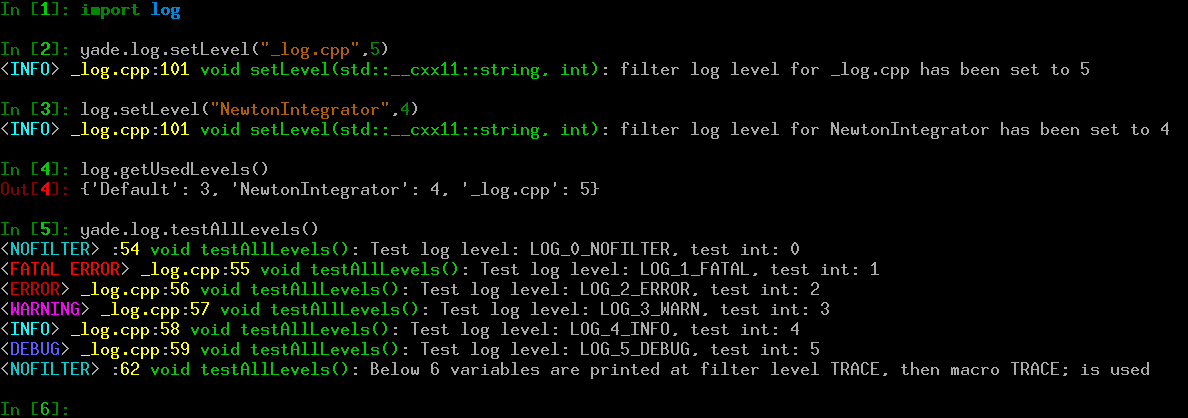

Figure imgLogging shows example use of logging framework. Usually a ClassName appears in place of _log.cpp shown on the screenshot. It is there because the yade.log module uses CREATE_CPP_LOCAL_LOGGER macro instead of the regular DECLARE_LOGGER and CREATE_LOGGER, which are discussed below.

Note

Default format of log message is:

<severity level> ClassName:LineNumber FunctionName: Log Message

special macro LOG_NOFILTER is printed without ClassName because it lacks one.

Config files can be saved and loaded via readConfigFile and saveConfigFile. The defaultConfigFileName is read upon startup if it exists. The filter level setting -f supplied from command line will override the setting in config file.

Log levels¶

Following debug levels are supported:

macro name |

filter name |

option |

explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Will print only the unfiltered messages. The LOG_NOFILTER macro is for

developer use only, so basically |

|

|

|

Will print only critical errors. Even a throw to yade python interface will not recover from this situation. This is usually followed by yade exiting to shell. |

|

|

|

Will also print errors which do not require to throw to yade python interface. Calculations will continue, but very likely the results will be all wrong. |

|

|

|

Will also print warnings about recoverable problems that you should be notified about (e.g., invalid value in a configuration file, so yade fell back to the default value). |

|

|

|

Will also print all informational messages (e.g. something was loaded, something was called, etc.). |

|

|

|

Will also print debug messages. A yade developer puts them everywhere, and yade user enables them on per-class basis to provide some extra debug info. |

|

|

|

Trace messages, they capture every possible detail about yade behavior. |

Yade default log level is yade.log.WARN which is the same as invoking yade -f3.

Setting a filter level¶

Warning

The messages (such as a << b << " message.") given as arguments to LOG_* macros are used only if the message passes the filter level. Do not use such messages to perform mission critical calculations.

There are two settings for the filter level, the Default level used when no ClassName (or "filename.cpp") specific filter is set and a filter level set for specific ClassName (or "filename.cpp"). They can be set with following means:

When starting yade with

yade -fNcommand, whereNsets theDefaultfilter level. The default value isyade.log.WARN(3).To change

Defaultfilter level during runtime invoke commandlog.setLevel("Default",value)orlog.setDefaultLogLevel(value):

Yade [1]: import log

Yade [2]: log.setLevel("Default",log.WARN)

Yade [3]: log.setLevel("Default",3)

Yade [4]: log.setDefaultLogLevel(log.WARN)

Yade [5]: log.setDefaultLogLevel(3)

To change filter level for

SomeClassinvoke command:

Yade [6]: import log

Yade [7]: log.setLevel("NewtonIntegrator",log.TRACE)

Yade [8]: log.setLevel("NewtonIntegrator",6)

To change the filter level for

"filename.cpp"use the name specified when creating it. For example manipulating filter log level of"_log.cpp"might look like following:

Yade [9]: import log

Yade [10]: log.getUsedLevels()

Out[10]: {'Default': 3, 'NewtonIntegrator': 6}

Yade [11]: log.setLevel("_log.cpp",log.WARN)

Yade [12]: log.getUsedLevels()

Out[12]: {'Default': 3, 'NewtonIntegrator': 6, '_log.cpp': 3}

Yade [13]: log.getAllLevels()["_log.cpp"]

Out[13]: 3

Debug macros¶

To enable debugging for particular class the DECLARE_LOGGER; macro should be put in class definition inside header to create a separate named logger for that class. Then the CREATE_LOGGER(ClassName); macro must be used in the class implementation .cpp file to create the static variable. Sometimes a logger is necessary outside the class, such named logger can be created inside a .cpp file and by convention its name should correspond to the name of the file, use the macro CREATE_CPP_LOCAL_LOGGER("filename.cpp"); for this. On rare occasions logging is necessary inside .hpp file outside of a class (where the local class named logger is unavailable), then the solution is to use LOG_NOFILTER(…) macro, because it is the only one that can work without a named logger. If the need arises this solution can be improved, see Logging.cpp for details.

All debug macros (LOG_TRACE, LOG_DEBUG, LOG_INFO, LOG_WARN, LOG_ERROR, LOG_FATAL, LOG_NOFILTER) listed in section above accept the std::ostream syntax inside the brackets, such as LOG_TRACE( a << b << " text" ). The LOG_NOFILTER is special because it is always printed regardless of debug level, hence it should be used only in development branches.

Additionally seven macros for printing variables at LOG_TRACE level are available: TRVAR1, TRVAR2, TRVAR3, TRVAR4, TRVAR5, TRVAR6 and TRVARn. They print the variables, e.g.: TRVAR3(testInt,testStr,testReal); or TRVARn((testInt)(testStr)(testReal)). See function testAllLevels for example use.

The macro TRACE; prints a "Been here" message at TRACE log filter level, and can be used for quick debugging.

Utility debug macros¶

The LOG_TIMED_* family of macros:

In some situations it is useful to debug variables inside a very fast, or maybe a multithreaded, loop. In such situations it would be useful to:

Avoid spamming console with very fast printed messages and add some print timeout to them, preferably specified with units of seconds or milliseconds.

Make sure that each separate thread has opportunity to print message, without interleaving such messages with other threads.

To use above functionality one must #include <lib/base/LoggingUtils.hpp> in the .cpp file which provides the LOG_TIMED_* and TIMED_TRVAR* macro family. Example usage can be found in function testTimedLevels.

To satisfy the first requirement all LOG_TIMED_* macros accept two arguments, where the first argument is the wait timeout, using standard C++14 / C++20 time units, example use is LOG_TIMED_INFO( 2s , "test int: " << testInt++); to print every 2 seconds. But only seconds and milliseconds are accepted (this can be changed if necessary).

To satisfy the second requirement a thread_local static Timer variable is used. This way each thread in a parallel loop can print a message every 500ms or 10s e.g. in this parallel loop. The time of last print to console is stored independently for each thread and an extra code block which checks time is added. It means that a bit more checks are done than typical LOG_* which only perform an integer comparison to check filter level. Therefore suggested use is only during heavy debugging. When debugging is finished then better to remove them.

Note

The *_TRACE family of macros are removed by compiler during the release builds, because the default -DMAX_LOG_LEVEL is 5. So those are very safe to use, but to have them working locally make sure to compile yade with cmake -DMAX_LOG_LEVEL=6 option.

The LOG_ONCE_* family of macros:

In a similar manner a LOG_ONCE_* and ONCE_TRVAR* family of macros is provided inside file LoggingUtils.hpp. Then the message is printed only once.

All debug macros are summarized in the table below:

macro name |

explanation |

|---|---|

|

Declares logger variable inside class definition in |

|

Creates logger static variable (with name |

|

Creates logger static variable (with name |

|

Creates logger static variable outside of any class (with name |

LOG_TRACE, LOG_TIMED_TRACE, LOG_ONCE_TRACE,LOG_DEBUG, LOG_TIMED_DEBUG, LOG_ONCE_DEBUG,LOG_INFO, LOG_TIMED_INFO, LOG_ONCE_INFO,LOG_WARN, LOG_TIMED_WARN, LOG_ONCE_WARN,LOG_ERROR, LOG_TIMED_ERROR, LOG_ONCE_ERROR,LOG_FATAL, LOG_TIMED_FATAL, LOG_ONCE_FATAL,LOG_NOFILTER, LOG_TIMED_NOFILTER, LOG_ONCE_NOFILTER |

Prints message using

std::ostream syntax, like:LOG_TRACE( a << b << " text" )LOG_TIMED_TRACE( 5s , a << b << " text" ); , prints every 5 secondsLOG_TIMED_DEBUG( 500ms , a );, prints every 500 millisecondsLOG_ONCE_TRACE( a << b << " text" ); , prints just onceLOG_ONCE_DEBUG( a );, prints only once |

TRVAR1, TIMED_TRVAR1, ONCE_TRVAR1,TRVAR2, TIMED_TRVAR2, ONCE_TRVAR2,TRVAR3, TIMED_TRVAR3, ONCE_TRVAR3,TRVAR4, TIMED_TRVAR4, ONCE_TRVAR4,TRVAR5, TIMED_TRVAR5, ONCE_TRVAR5,TRVAR6, TIMED_TRVAR6, ONCE_TRVAR6,TRVARn, TIMED_TRVARn, ONCE_TRVARn |

Prints provided variables like:

TRVAR3(testInt,testStr,testReal);TRVARn((testInt)(testStr)(testReal));TIMED_TRVAR3( 10s , testInt , testStr , testReal);ONCE_TRVARn( (testInt)(testStr)(testReal));See file py/_log.cpp for example use.

|

|

Prints a |

LOG_TIMED_6, LOG_6_TRACE, LOG_ONCE_6,LOG_TIMED_5, LOG_5_DEBUG, LOG_ONCE_5,LOG_TIMED_4, LOG_4_INFO, LOG_ONCE_4,LOG_TIMED_3, LOG_3_WARN, LOG_ONCE_3,LOG_TIMED_2, LOG_2_ERROR, LOG_ONCE_2,LOG_TIMED_1, LOG_1_FATAL, LOG_ONCE_1,LOG_TIMED_0, LOG_0_NOFILTER, LOG_ONCE_0,LOG_TIMED_6_TRACE, LOG_6, LOG_ONCE_6_TRACE,LOG_TIMED_5_DEBUG, LOG_5, LOG_ONCE_5_DEBUG,LOG_TIMED_4_INFO, LOG_4, LOG_ONCE_4_INFO,LOG_TIMED_3_WARN, LOG_3, LOG_ONCE_3_WARN,LOG_TIMED_2_ERROR, LOG_2, LOG_ONCE_2_ERROR,LOG_TIMED_1_FATAL, LOG_1, LOG_ONCE_1_FATAL,LOG_TIMED_0_NOFILTER, LOG_0 LOG_ONCE_0_NOFILTER, |

Additional macro aliases for easier use in editors with tab completion. They have have a filter level number in their name. |

Maximum log level¶

Using boost::log for log filtering means that each call to LOG_* macro must perform a single integer comparison to determine if the message passes current filter level. For production use calculations should be as fast as possible and this filtering is not optimal, because the macros are not optimized out, as they can be re-enabled with a simple call to log.setLevel("Default",log.TRACE) or log.setLevel("Default",6). The remedy is to use the cmake compilation option MAX_LOG_LEVEL=4 (or 3) which will remove macros higher than the specified level during compilation. The code will run slightly faster and the command log.setLevel("Default",6) will only print a warning that such high log level (which can be checked with log.getMaxLevel() call) is impossible to obtain with current build.

Note

At the time when logging was introduced into yade the speed-up gain was so small, that it turned out to be impossible to measure with yade -f0 --stdperformance command. Hence this option MAX_LOG_LEVEL was introduced only on principle.

The upside of this approach is that yade can be compiled in a non-debug build, and the log filtering framework can be still used.

Regression tests¶

Yade contains two types of regression tests, some are unit tests while others are testing more complex simulations. Although both types can be considered regression tests, the usage is that we name the first simply “regression tests”, while the latest are called “check tests”. Both series of tests can be ran at yade startup by passing the options “test” or “checkall”

yade --test

yade --checkall

The yade --checkall is a complete check. To skip checks lasting more than 30 seconds one can use this command

yade --check

Unit regression tests¶

Unit regression tests are testing the output of individual functors and engines in well defined conditions. They are defined in the folder py/tests/. The purpose of unit testing is to make sure that the behaviour of the most important classes remains correct during code development. Since they test classes one by one, unit tests can’t detect problems coming from the interaction between different engines in a typical simulation. That is why check tests have been introduced.

To add a new test, the following steps must be performed:

Place a new file such as py/tests/dummyTest.py.

Add the file name such as

dummyTestto the py/tests/__init__.py file.If necessary modify the

importandallModuleslines in py/tests/__init__.py.According to instructions in python unittest documentation use commands such as

self.assertTrue(…),self.assertFalse(…)orself.assertRaises(…,…)to report possible errors.

Note

It is important that all variables used in the test are stored inside the class (using the self. accessor), and that all preparations are done inside the function setUp().

Check tests¶

Check tests (also see README) perform comparisons of simulation results between different versions of yade, as discussed here. They differ with regression tests in the sense that they simulate more complex situations and combinations of different engines, and usually don’t have a mathematical proof (though there is no restriction on the latest). They compare the values obtained in version N with values obtained in a previous version or any other “expected” results. The reference values must be hardcoded in the script itself or in data files provided with the script. Check tests are based on regular yade scripts, so that users can easily commit their own scripts to trunk in order to get some automatized testing after commits from other developers.

When check fails the script should return an error message via python command raise YadeCheckError(messageString) telling what went wrong. If the script itself fails for some reason and can’t generate an output, the log will contain only “scriptName failure”. If the script defines differences on obtained and awaited data, it should print some useful information about the problem. After this occurs, the automatic test will stop the execution with error message.

An example dummy check test scripts/checks-and-tests/checks/checkTestDummy.py demonstrates a minimal empty test. A little more functional example check test can be found in scripts/checks-and-tests/checks/checkTestTriax.py. It shows results comparison, output, and how to define the path to data files using checksPath.

Users are encouraged to add their own scripts into the scripts/checks-and-tests/checks/ folder. Discussion of some specific checktests design in questions and answers is welcome. Note that re-compiling is required before the newly added scripts can be launched by yade --check (or direct changes have to be performed in “lib” subfolders).

A check test should never need more than a few seconds to run. If your typical script needs more, try to reduce the number of elements or the number of steps.

To add a new check, the following steps must be performed:

Place a new file such as scripts/checks-and-tests/checks/checkTestDummy.py,

Inside the new script use

checksPathwhen it is necessary to load some data file, like scripts/checks-and-tests/checks/data/100spheresWhen error occurs raise exception with command

raise YadeCheckError(messageString)

It is recommended to run simulation for certain number of steps before checking the condition (O.run(Nsteps,wait = True)) rather than pausing simulation with O.pause(). The latter may cause segmentation fault during checks (related to execfile limitation described in the warning below).

Warning

Due to the limitation of execfile the local variables created in one check script are passed down to the check scripts executed after it. Hence creating a local variable in one script called e.g. Body will break the scripts executed after it, when they will try to create a new Body(). The workaround is to use unique non-trivial variable names in the check scripts.

GUI Tests¶

In order to add a new GUI test one needs to add a file to scripts/checks-and-tests/gui directory. File must be named according to the following convention:

testGuiName.py with an appropriate test Name in place (the testGui.sh script is searching

for files matching this pattern).

The scripts/checks-and-tests/gui/testGuiBilliard.py may serve as a boilerplate example. The important “extra” parts of the code (taken from e.g. example directory) are:

from testGuiHelper import TestGUIHelperscr = TestGUIHelper("Billiard"), make sure to put the chosen testNamein place ofBilliard.Establish a reasonable value of

guiIterPeriodwhich makes the test finish in less than 30 seconds.Inside

O.enginesthere has to be a call at the end of the loop toPyRunner(iterPeriod=guiIterPeriod, command='scr.screenshotEngine()').The last command in the script should be

O.run(guiIterPeriod * scr.getTestNum() + 1)to start the test process.Make sure to push to yade-data repository the reference screenshots (for dealing with

./datadir see Yade on GitLab). These screenshots can be also obtained from artifacts by clicking “Download” button in the gitlab pipeline, next to the “Browse” button in the right pane.

These tests can be run locally, after adjusting the paths at the start of testGui.sh script. Two modes of operation are possible:

Launch on the local desktop via command:

scripts/checks-and-tests/gui/testGui.sh, in this case the screenshots will be different from those used during the test.Or launch inside a virtual xserver via command:

xvfb-run -a -s "-screen 0 1600x1200x24" scripts/checks-and-tests/gui/testGui.sh, then the screenshots will be similar to those used in the test, but still there may be some differences in the font size. In such case it is recommended to use the reference screenshots downloaded from the artifacts in the gitlab pipeline (see point 6. above).

Care should be taken to not use random colors of bodies used in the test. Also no windows such as 3d View or Inspector view should be opened in the script testGuiName.py, because they are opened during the test by the TestGUIHelper class.

Note

It is not possible to call GUI tests from a call such as yade --test because of the necessity to launch YADE inside a virtual xserver.

Conventions¶

The following coding rules should be respected; documentation is treated separately.

general

C++ source files have

.hppand.cppextensions (for headers and implementation, respectively). In rare cases.ippis used for pure template code.All header files should have the

#pragma oncemultiple-inclusion guard.Do not type

using namespace …in header files, this can lead to obscure bugs due to namespace pollution.Avoid

using std::somethingin.hppfiles. Feel free to use them as much as you like inside.cppfiles. But remember that the usual problems with this practice still apply: wrong type or function might be used instead of the one that you would expect. But since it’s limited to a single.cppfile, it will be easier to debug and the convenience might outweight the associated dangers.Use tabs for indentation. While this is merely visual in

C++, it has semantic meaning in python; inadvertently mixing tabs and spaces can result in syntax errors.

capitalization style

Types should be always capitalized. Use CamelCase for composed class and typenames (

GlobalEngine). Underscores should be used only in special cases, such as functor names.Class data members and methods must not be capitalized, composed names should use lowercase camelCase (

glutSlices). The same applies for functions in python modules.Preprocessor macros are uppercase, separated by underscores; those that are used outside the core take (with exceptions) the form

YADE_*, such as YADE_CLASS_BASE_DOC_* macro family.

programming style

Be defensive, if it has no significant performance impact. Use assertions abundantly: they don’t affect performance (in the optimized build) and make spotting error conditions much easier.

Use

YADE_CASTandYADE_PTR_CASTwhere you want type-check during debug builds, but fast casting in optimized build.Initialize all class variables in the default constructor. This avoids bugs that may manifest randomly and are difficult to fix. Initializing with NaN’s will help you find otherwise unitialized variable. (This is taken care of by YADE_CLASS_BASE_DOC_* macro family macros for user classes)

Using clang-format¶

The file .clang-format contains the config which should produce always the same results. It works with clang-format --version >= 10. The aim is to eliminate commits that change formatting. The script scripts/clang-formatter.sh can be invoked on either file or a directory and will do the reformatting. Usually this can be integrated with the editor, see clang-format documentation (except that for vim py3f command has to be used), and in kdevelop it is added as a custom formatter.

The script scripts/python-formatter.sh applies our coding conventions to formatting of python scripts. It should be used before committing changes to python scripts.

For more help see:

Sometimes it is useful to disable formatting in a small section of the file. In order to do so, put the guards around this section:

In

C++use:// clang-format off …… // clang-format on

In

Pythonuse:# yapf: disable …… # yapf: enable

Class naming¶

Although for historical reasons the naming scheme is not completely consistent, these rules should be obeyed especially when adding a new class.

- GlobalEngines and PartialEngines

GlobalEngines should be named in a way suggesting that it is a performer of certain action (like ForceResetter, InsertionSortCollider, Recorder); if this is not appropriate, append the

Engineto the characteristics name (e.g. GravityEngine). PartialEngines have no special naming convention different from GlobalEngines.- Dispatchers

Names of all dispatchers end in

Dispatcher. The name is composed of type it creates or, in case it doesn’t create any objects, its main characteristics. Currently, the following dispatchers [2] are defined:

dispatcher

arity

dispatch types

created type

functor type

functor prefix

1

Bo12 (symetric)

2 × Shape

Ig22 (symetric)

2 × Material

Ip22 (asymetric)

(none)

Law2Respective abstract functors for each dispatchers are BoundFunctor, IGeomFunctor, IPhysFunctor and LawFunctor.

- Functors

Functor name is composed of 3 parts, separated by underscore.

prefix, composed of abbreviated functor type and arity (see table above)

Types entering the dispatcher logic (1 for unary and 2 for binary functors)

Return type for functors that create instances, simple characteristics for functors that don’t create instances.

To give a few examples:

Bo1_Sphere_Aabb is a BoundFunctor which is called for Sphere, creating an instance of Aabb.

Ig2_Facet_Sphere_ScGeom is binary functor called for Facet and Sphere, creating and instace of ScGeom.

Law2_ScGeom_CpmPhys_Cpm is binary functor (LawFunctor) called for types ScGeom (Geom) and CpmPhys.

Not considering OpenGL dispatchers, which might be replaced by regular virtual functions in the future.

Documentation¶

Documenting code properly is one of the most important aspects of sustained development.

Read it again.

Most code in research software like Yade is not only used, but also read, by developers or even by regular users. Therefore, when adding new class, always mention the following in the documentation:

purpose

details of the functionality, unless obvious (algorithms, internal logic)

limitations (by design, by implementation), bugs

bibliographical reference, if using non-trivial published algorithms (see below)

references to other related classes

hyperlinks to bugs, blueprints, wiki or mailing list about this particular feature.

As much as it is meaningful, you should also

update any other documentation affected

provide a simple python script demonstrating the new functionality in

scripts/test.

Sphinx documentation¶

Most c++ classes are wrapped in Python, which provides good introspection and interactive documentation (try writing Material? in the ipython prompt; or help(CpmState)).

Syntax of documentation is ReST (reStructuredText, see reStructuredText Primer). It is the same for c++ and python code.

Documentation of c++ classes exposed to python is given as 3rd argument to YADE_CLASS_BASE_DOC_* macro family introduced below.

Python classes/functions are documented using regular python docstrings. Besides explaining functionality, meaning and types of all arguments should also be documented. Short pieces of code might be very helpful. See the utils module for an example.

Note

Use C++ string literal when writing docstrings in C++. By convention the R"""(raw text)""" is used. For example see here and here.

Note

Remember that inside C++ docstrings it is possible to invoke python commands which are executed by yade when documentation is being compiled. For example compare this source docstring with the final effect.

In addition to standard ReST syntax, yade provides several shorthand macros:

:yref:creates hyperlink to referenced term, for instance:

:yref:`CpmMat`

becomes CpmMat; link name and target can be different:

:yref:`Material used in the CPM model<CpmMat>`

yielding Material used in the CPM model.

:ysrc:creates hyperlink to file within the source tree (to its latest version in the repository), for instance core/Cell.hpp. Just like with

:yref:, alternate text can be used with:ysrc:`Link text<target/file>`

like this. This cannot be used to link to a specified line number, since changing the file will cause the line numbers to become outdated. To link to a line number use

:ysrccommit:described below.:ysrccommit:creates hyperlink to file within the source tree at the specified commit hash. This allows to link to the line numbers using for example

#L121at the end of the link. Use it just like the:ysrc:except that commit hash must be provided at the beginning::ysrccommit:`Link text<commithash/target/file#Lnumber>` :ysrccommit:`default engines<775ae7436/py/__init__.py.in#L112>`

becomes default engines.

- Linking to

inheritanceGraph* To link to an inheritance graph of some base class a global anchor is created with name

inheritanceGraph*added in front of the class name, for example:ref:`Shape<inheritanceGraphShape>`yields link to inheritance graph of Shape.|ycomp|is used in attribute description for those that should not be provided by the user, but are auto-computed instead;

|ycomp|expands to (auto-computed).|yupdate|marks attributes that are periodically updated, being subset of the previous.

|yupdate|expands to (auto-updated).$...$delimits inline math expressions; they will be replaced by:

:math:`...`

and rendered via LaTeX. To write a single dollar sign, escape it with backslash

\$.Displayed mathematics (standalone equations) can be inserted as explained in Math support for HTML outputs in Sphinx.

As a reminder in the standard ReST syntax the references are:

:ref:is the the standard restructured text reference to an anchor placed elsewere in the text. For instance an anchor

.. _NumericalDamping:is placed in formulation.rst then it is linked to with:ref:`NumericalDamping`inside the source code... _anchor-name:is used to place anchors in the text, to be referenced from elsewhere in the text. Symbol

_is forbidden in the anchor name, because it has a special meaning:_anchorspecifies anchor, whileanchor_links to it, see below.anchor-name_is used to place a link to anchor within the same file. It is a shorter form compared to the one which works between different files:

:ref:. For example usage on anchorimgQtGuisee here and here.

Note

The command :scale: NN % (with percent) does not work well with .html + .pdf output, better to specify :width: NN cm. Then it is the same size in .html and .pdf.. For example see here which becomes this picture. But bear in mind that maximum picture width in .pdf is 16.2 cm.

Bibliographical references¶

As in any scientific documentation, references to publications are very important. To cite an article, first add it in BibTeX format to files doc/references.bib or doc/yade-*.bib depending whether that reference used Yade (the latter cases) or not (the former). Please adhere to the following conventions:

Keep entries in the form

Author2008(Authoris the first author),Author2008betc if multiple articles from one author;Try to fill mandatory fields for given type of citation;

Do not use

\'{i}funny escapes for accents, since they will not work with the HTML output; put everything in straight utf-8.

In your docstring, the Author2008 article can be then cited by [Author2008]_; for example:

According to [Allen1989]_, the integration scheme …

will be rendered as

According to [Allen1989], the integration scheme …

Separate class/function documentation¶

Some c++ might have long or content-rich documentation, which is rather inconvenient to type in the c++ source itself as string literals. Yade provides a way to write documentation separately in py/_extraDocs.py file: it is executed after loading c++ plugins and can set __doc__ attribute of any object directly, overwriting docstring from c++. In such (exceptional) cases:

Provide at least a brief description of the class in the c++ code nevertheless, for people only reading the code.

Add notice saying “This class is documented in detail in the py/_extraDocs.py file”.

Add documentation to py/_extraDocs.py in this way:

module.YourClass.__doc__=''' This is the docstring for YourClass. Class, methods and functions can be documented this way. .. note:: It can use any syntax features you like. '''

Note

Boost::python embeds function signatures in the docstring (before the one provided by the user). Therefore, before creating separate documentation of your function, have a look at its __doc__ attribute and copy the first line (and the blank line afterwards) in the separate docstring. The first line is then used to create the function signature (arguments and return value).

Internal c++ documentation¶

doxygen was used for automatic generation of c++ code. Since user-visible classes are defined with sphinx now, it is not meaningful to use doxygen to generate overall documentation. However, take care to document well internal parts of code using regular comments, including public and private data members.

Support framework¶

Besides the framework provided by the c++ standard library (including STL), boost and other dependencies, Yade provides its own specific services.

Pointers¶

Typecasting¶

Frequently, pointers have to be typecast; there is choice between static and dynamic casting.

dynamic_cast(dynamic_pointer_castfor ashared_ptr) assures cast admissibility by checking runtime type of its argument and returns NULL if the cast is invalid; such check obviously costs time. Invalid cast is easily caught by checking whether the pointer is NULL or not; even if such check (e.g.assert) is absent, dereferencing NULL pointer is easily spotted from the stacktrace (debugger output) after crash. Moreover,shared_ptrchecks that the pointer is non-NULL before dereferencing in debug build and aborts with “Assertion `px!=0’ failed.” if the check fails.static_castis fast but potentially dangerous (static_pointer_castforshared_ptr). Static cast will return non-NULL pointer even if types don’t allow the cast (such as casting fromState*toMaterial*); the consequence of such cast is interpreting garbage data as instance of the class cast to, leading very likely to invalid memory access (segmentation fault, “crash” for short).

To have both speed and safety, Yade provides 2 macros:

YADE_CASTexpands to

static_castin optimized builds and todynamic_castin debug builds.YADE_PTR_CASTexpands to

static_pointer_castin optimized builds and todynamic_pointer_castin debug builds.

Basic numerics¶

The floating point type to use in Yade is Real, which is by default typedef for double (64 bits, 15 decimal places). [4]

Yade uses the Eigen library for computations. It provides classes for 2d and 3d vectors, quaternions and 3x3 matrices templated by number type; their specialization for the Real type are typedef’ed with the “r” suffix, and occasionally useful integer types with the “i” suffix:

Vector2r,Vector2i

Vector3r,Vector3i

Quaternionr

Matrix3r

Yade additionally defines a class named Se3r, which contains spatial position (Vector3r Se3r::position) and orientation (Quaternionr Se3r::orientation), since they are frequently used one with another, and it is convenient to pass them as single parameter to functions.

See high precision documentation for additional details.

Eigen provides full rich linear algebra functionality. Some code further uses the [cgal] library for computational geometry.

In Python, basic numeric types are wrapped and imported from the yade.minieigenHP module; the types drop the r type qualifier at the end, the syntax is otherwise similar. Se3r is not wrapped at all, only converted automatically, rarely as it is needed, from/to a (Vector3,Quaternion) tuple/list. See high precision section for more details.

# cross product

Yade [14]: Vector3(1,2,3).cross(Vector3(0,0,1))

Out[14]: Vector3(2,-1,0)

# construct quaternion from axis and angle

Yade [15]: Quaternion(Vector3(0,0,1),pi/2)

Out[15]: Quaternion((0,0,1),1.570796326794896558)

Note

Quaternions are internally stored as 4 numbers. Their usual human-readable representation is, however, (normalized) axis and angle of rotation around that axis, and it is also how they are input/output in Python. Raw internal values can be accessed using the [0] … [3] element access (or .W(), .X(), .Y() and .Z() methods), in both c++ and Python.

Run-time type identification (RTTI)¶

Since serialization and dispatchers need extended type and inheritance information, which is not sufficiently provided by standard RTTI. Each yade class is therefore derived from Factorable and it must use macro to override its virtual functions providing this extended RTTI:

YADE_CLASS_BASE_DOC(Foo,Bar Baz,"Docstring") creates the following virtual methods (mediated via the REGISTER_CLASS_AND_BASE macro, which is not user-visible and should not be used directly):

std::string getClassName()returning class name (Foo) as string. (There is thetypeid(instanceOrType).name()standard c++ construct, but the name returned is compiler-dependent.)unsigned getBaseClassNumber()returning number of base classes (in this case, 2).std::string getBaseClassName(unsigned i=0)returning name of i-th base class (here,Barfor i=0 andBazfor i=1).

Warning

RTTI relies on virtual functions; in order for virtual functions to work, at least one virtual method must be present in the implementation (.cpp) file. Otherwise, virtual method table (vtable) will not be generated for this class by the compiler, preventing virtual methods from functioning properly.

Some RTTI information can be accessed from python:

Yade [16]: yade.system.childClasses('Shape')

Out[16]:

{'Box',

'ChainedCylinder',

'Clump',

'Cylinder',

'DeformableCohesiveElement',

'DeformableElement',

'Facet',

'FluidDomainBbox',

'GridConnection',

'GridNode',

'LevelSet',

'Lin4NodeTetra',

'Lin4NodeTetra_Lin4NodeTetra_InteractionElement',

'Node',

'PFacet',

'Polyhedra',

'PotentialBlock',

'PotentialParticle',

'Sphere',

'Subdomain',

'Tetra',

'Wall'}

Yade [17]: Sphere().__class__.__name__ ## getClassName()

Out[17]: 'Sphere'

Serialization¶

Serialization serves to save simulation to file and restore it later. This process has several necessary conditions:

classes know which attributes (data members) they have and what are their names (as strings);

creating class instances based solely on its name;

knowing what classes are defined inside a particular shared library (plugin).

This functionality is provided by 3 macros and 4 optional methods; details are provided below.

Serializable::preLoad,Serializable::preSave,Serializable::postLoad,Serializable::postSavePrepare attributes before serialization (saving) or deserialization (loading) or process them after serialization or deserialization.

YADE_CLASS_BASE_DOC_*Inside the class declaration (i.e. in the

.hppfile within theclass Foo { /* … */};block). See Attribute registration.Enumerate class attributes that should be saved and loaded; associate each attribute with its literal name, which can be used to retrieve it. See YADE_CLASS_BASE_DOC_* macro family.

Additionally documents the class in python, adds methods for attribute access from python, and documents each attribute.

REGISTER_SERIALIZABLEIn header file, but after the class declaration block. See Class factory.

Associate literal name of the class with functions that will create its new instance (

ClassFactory).Must be declared inside

namespace yade.YADE_PLUGINIn the implementation

.cppfile. See Plugin registration.Declare what classes are declared inside a particular plugin at time the plugin is being loaded (yade startup).

Must be declared inside

namespace yade.

Attribute registration¶

All (serializable) types in Yade are one of the following:

Type deriving from Serializable, which provide information on how to serialize themselves via overriding the

Serializable::registerAttributesmethod; it declares data members that should be serialzed along with their literal names, by which they are identified. This method then invokesregisterAttributesof its base class (untilSerializableitself is reached); in this way, derived classes properly serialize data of their base classes.This funcionality is hidden behind the macro YADE_CLASS_BASE_DOC_* macro family used in class declaration body (header file), which takes base class and list of attributes:

YADE_CLASS_BASE_DOC_ATTRS(ThisClass,BaseClass,"class documentation",((type1,attribute1,initValue1,,"Documentation for attribute 1"))((type2,attribute2,initValue2,,"Documentation for attribute 2")));

Note that attributes are encoded in double parentheses, not separated by commas. Empty attribute list can be given simply by

YADE_CLASS_BASE_DOC_ATTRS(ThisClass,BaseClass,"documentation",)(the last comma is mandatory), or by omitingATTRSfrom macro name and last parameter altogether.Fundamental type: strings, various number types, booleans,

Vector3rand others. Their “handlers” (serializers and deserializers) are defined inlib/serialization.Standard container of any serializable objects.

Shared pointer to serializable object.

Yade uses the excellent boost::serialization library internally for serialization of data.

Note

YADE_CLASS_BASE_DOC_ATTRS also generates code for attribute access from python; this will be discussed later. Since this macro serves both purposes, the consequence is that attributes that are serialized can always be accessed from python.

Yade also provides callback for before/after (de) serialization, virtual functions Serializable::preProcessAttributes and Serializable::postProcessAttributes, which receive one bool deserializing argument (true when deserializing, false when serializing). Their default implementation in Serializable doesn’t do anything, but their typical use is:

converting some non-serializable internal data structure of the class (such as multi-dimensional array, hash table, array of pointers) into a serializable one (pre-processing) and fill this non-serializable structure back after deserialization (post-processing); for instance, InteractionContainer uses these hooks to ask its concrete implementation to store its contents to a unified storage (

vector<shared_ptr<Interaction> >) before serialization and to restore from it after deserialization.precomputing non-serialized attributes from the serialized values; e.g. Facet computes its (local) edge normals and edge lengths from vertices’ coordinates.

Class factory¶

Each serializable class must use REGISTER_SERIALIZABLE, which defines function to create that class by ClassFactory. ClassFactory is able to instantiate a class given its name (as string), which is necessary for deserialization.

Although mostly used internally by the serialization framework, programmer can ask for a class instantiation using shared_ptr<Factorable> f=ClassFactory::instance().createShared("ClassName");, casting the returned shared_ptr<Factorable> to desired type afterwards. Serializable itself derives from Factorable, i.e. all serializable types are also factorable.

Note

Both macros REGISTER_SERIALIZABLE and YADE_PLUGIN have to be declared inside yade namespace.

Plugin registration¶

Yade loads dynamic libraries containing all its functionality at startup. ClassFactory must be taught about classes each particular file provides. YADE_PLUGIN serves this purpose and, contrary to YADE_CLASS_BASE_DOC_* macro family, must be placed in the implementation (.cpp) file, inside yade namespace. It simply enumerates classes that are provided by this file:

YADE_PLUGIN((ClassFoo)(ClassBar));

Note

You must use parentheses around the class name even if there is only one class (preprocessor limitation): YADE_PLUGIN((classFoo));. If there is no class in this file, do not use this macro at all.

Internally, this macro creates function registerThisPluginClasses_ declared specially as __attribute__((constructor)) (see GCC Function Attributes); this attributes makes the function being executed when the plugin is loaded via dlopen from ClassFactory::load(...). It registers all factorable classes from that file in the Class factory.

Note

Classes that do not derive from Factorable, such as Shop or SpherePack, are not declared with YADE_PLUGIN.

This is an example of a serializable class header:

namespace yade {

/*! Homogeneous gravity field; applies gravity×mass force on all bodies. */

class GravityEngine: public GlobalEngine{

public:

virtual void action();

// registering class and its base for the RTTI system

YADE_CLASS_BASE_DOC_ATTRS(GravityEngine,GlobalEngine,

// documentation visible from python and generated reference documentation

"Homogeneous gravity field; applies gravity×mass force on all bodies.",

// enumerating attributes here, include documentation

((Vector3r,gravity,Vector3r::Zero(),"acceleration, zero by default [kgms⁻²]"))

);

};

// registration function for ClassFactory

REGISTER_SERIALIZABLE(GravityEngine);

} // namespace yade

and this is the implementation:

#include <pkg/common/GravityEngine.hpp>

#include <core/Scene.hpp>

namespace yade {

// registering the plugin

YADE_PLUGIN((GravityEngine));

void GravityEngine::action(){

/* do the work here */

}

} // namespace yade

We can create a mini-simulation (with only one GravityEngine):

Yade [18]: O.engines=[GravityEngine(gravity=Vector3(0,0,-9.81))]

Yade [19]: O.save('abc.xml')

and the XML save looks like this:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" standalone="yes" ?>

<!DOCTYPE boost_serialization>

<boost_serialization signature="serialization::archive" version="19">

<scene class_id="0" tracking_level="0" version="1">

<px class_id="1" tracking_level="1" version="0" object_id="_0">

<Serializable class_id="2" tracking_level="1" version="0" object_id="_1"></Serializable>

<dt>1.00000000000000002e-08</dt>

<iter>0</iter>

<subStepping>0</subStepping>

<subStep>-1</subStep>

<time>0.00000000000000000e+00</time>

<speed>0.00000000000000000e+00</speed>

<stopAtIter>0</stopAtIter>

<stopAtTime>0.00000000000000000e+00</stopAtTime>

<isPeriodic>0</isPeriodic>

<trackEnergy>0</trackEnergy>

<doSort>0</doSort>

<runInternalConsistencyChecks>1</runInternalConsistencyChecks>

<selectedBody>-1</selectedBody>

<subdomain>0</subdomain>

<subD class_id="3" tracking_level="0" version="1">

<px class_id="4" tracking_level="1" version="0" object_id="_2">

<Serializable object_id="_3"></Serializable>

<color class_id="5" tracking_level="0" version="0">

<x>1.00000000000000000e+00</x>

<y>1.00000000000000000e+00</y>

<z>1.00000000000000000e+00</z>

</color>

<wire>0</wire>

<highlight>0</highlight>

</px>

</subD>

<tags class_id="6" tracking_level="0" version="0">

<count>5</count>

<item_version>0</item_version>

<item>author=root~(root@runner-jzdhzrer-project-10133144-concurrent-1)</item>

<item>isoTime=20260115T042329</item>

<item>id=20260115T042329p37</item>

<item>d.id=20260115T042329p37</item>

<item>id.d=20260115T042329p37</item>

</tags>

<engines class_id="7" tracking_level="0" version="0">

<count>1</count>

<item_version>1</item_version>

<item class_id="8" tracking_level="0" version="1">

<px class_id="10" class_name="yade::GravityEngine" tracking_level="1" version="0" object_id="_4">

<FieldApplier class_id="11" tracking_level="1" version="0" object_id="_5">

<GlobalEngine class_id="12" tracking_level="1" version="0" object_id="_6">

<Engine class_id="9" tracking_level="1" version="0" object_id="_7">

<Serializable object_id="_8"></Serializable>

<dead>0</dead>

<ompThreads>-1</ompThreads>

<label></label>

</Engine>

</GlobalEngine>

</FieldApplier>

<gravity>

<x>0.00000000000000000e+00</x>

<y>0.00000000000000000e+00</y>

<z>-9.81000000000000050e+00</z>

</gravity>

<mask>0</mask>

<warnOnce>1</warnOnce>

</px>

</item>

</engines>

<_nextEngines>

<count>0</count>

<item_version>1</item_version>

</_nextEngines>

<bodies class_id="13" tracking_level="0" version="1">

<px class_id="14" tracking_level="1" version="0" object_id="_9">

<Serializable object_id="_10"></Serializable>

<body class_id="15" tracking_level="0" version="0">

<count>0</count>

<item_version>1</item_version>

</body>

<insertedBodies>

<count>0</count>

<item_version>0</item_version>

</insertedBodies>

<erasedBodies>

<count>0</count>

<item_version>0</item_version>

</erasedBodies>

<realBodies>

<count>0</count>

<item_version>0</item_version>

</realBodies>

<useRedirection>0</useRedirection>

<enableRedirection>1</enableRedirection>

<subdomainBodies>

<count>0</count>

<item_version>0</item_version>

</subdomainBodies>

</px>

</bodies>

<interactions class_id="17" tracking_level="0" version="1">

<px class_id="18" tracking_level="1" version="0" object_id="_11">

<Serializable object_id="_12"></Serializable>

<interaction class_id="19" tracking_level="0" version="0">

<count>0</count>

<item_version>1</item_version>

</interaction>

<serializeSorted>0</serializeSorted>

<dirty>1</dirty>

</px>

</interactions>

<energy class_id="20" tracking_level="0" version="1">

<px class_id="21" tracking_level="1" version="0" object_id="_13">

<Serializable object_id="_14"></Serializable>

<energies class_id="22" tracking_level="0" version="0">

<size>0</size>

</energies>

<names class_id="23" tracking_level="0" version="0">

<count>0</count>

<item_version>0</item_version>

</names>

<resetStep>

<count>0</count>

</resetStep>

</px>

</energy>

<materials class_id="25" tracking_level="0" version="0">

<count>0</count>

<item_version>1</item_version>

</materials>

<bound class_id="26" tracking_level="0" version="1">

<px class_id="-1"></px>

</bound>

<cell class_id="28" tracking_level="0" version="1">

<px class_id="29" tracking_level="1" version="0" object_id="_15">

<Serializable object_id="_16"></Serializable>

<trsf class_id="30" tracking_level="0" version="0">

<m00>1.00000000000000000e+00</m00>

<m01>0.00000000000000000e+00</m01>

<m02>0.00000000000000000e+00</m02>

<m10>0.00000000000000000e+00</m10>

<m11>1.00000000000000000e+00</m11>

<m12>0.00000000000000000e+00</m12>

<m20>0.00000000000000000e+00</m20>

<m21>0.00000000000000000e+00</m21>

<m22>1.00000000000000000e+00</m22>

</trsf>

<refHSize>

<m00>1.00000000000000000e+00</m00>

<m01>0.00000000000000000e+00</m01>

<m02>0.00000000000000000e+00</m02>

<m10>0.00000000000000000e+00</m10>

<m11>1.00000000000000000e+00</m11>

<m12>0.00000000000000000e+00</m12>

<m20>0.00000000000000000e+00</m20>

<m21>0.00000000000000000e+00</m21>

<m22>1.00000000000000000e+00</m22>

</refHSize>

<hSize>

<m00>1.00000000000000000e+00</m00>

<m01>0.00000000000000000e+00</m01>

<m02>0.00000000000000000e+00</m02>

<m10>0.00000000000000000e+00</m10>

<m11>1.00000000000000000e+00</m11>

<m12>0.00000000000000000e+00</m12>

<m20>0.00000000000000000e+00</m20>

<m21>0.00000000000000000e+00</m21>

<m22>1.00000000000000000e+00</m22>

</hSize>

<prevHSize>

<m00>1.00000000000000000e+00</m00>

<m01>0.00000000000000000e+00</m01>

<m02>0.00000000000000000e+00</m02>

<m10>0.00000000000000000e+00</m10>

<m11>1.00000000000000000e+00</m11>

<m12>0.00000000000000000e+00</m12>

<m20>0.00000000000000000e+00</m20>

<m21>0.00000000000000000e+00</m21>

<m22>1.00000000000000000e+00</m22>

</prevHSize>

<velGrad>

<m00>0.00000000000000000e+00</m00>

<m01>0.00000000000000000e+00</m01>

<m02>0.00000000000000000e+00</m02>

<m10>0.00000000000000000e+00</m10>

<m11>0.00000000000000000e+00</m11>

<m12>0.00000000000000000e+00</m12>

<m20>0.00000000000000000e+00</m20>

<m21>0.00000000000000000e+00</m21>

<m22>0.00000000000000000e+00</m22>

</velGrad>

<nextVelGrad>

<m00>0.00000000000000000e+00</m00>

<m01>0.00000000000000000e+00</m01>

<m02>0.00000000000000000e+00</m02>

<m10>0.00000000000000000e+00</m10>

<m11>0.00000000000000000e+00</m11>

<m12>0.00000000000000000e+00</m12>

<m20>0.00000000000000000e+00</m20>

<m21>0.00000000000000000e+00</m21>

<m22>0.00000000000000000e+00</m22>

</nextVelGrad>

<prevVelGrad>

<m00>0.00000000000000000e+00</m00>

<m01>0.00000000000000000e+00</m01>

<m02>0.00000000000000000e+00</m02>

<m10>0.00000000000000000e+00</m10>

<m11>0.00000000000000000e+00</m11>

<m12>0.00000000000000000e+00</m12>

<m20>0.00000000000000000e+00</m20>

<m21>0.00000000000000000e+00</m21>

<m22>0.00000000000000000e+00</m22>

</prevVelGrad>

<homoDeform>2</homoDeform>

<velGradChanged>0</velGradChanged>

<flipFlippable>0</flipFlippable>

</px>

</cell>

<miscParams class_id="31" tracking_level="0" version="0">

<count>0</count>

<item_version>1</item_version>

</miscParams>

<dispParams class_id="32" tracking_level="0" version="0">

<count>0</count>

<item_version>1</item_version>

</dispParams>

</px>

</scene>

</boost_serialization>

Warning

Since XML files closely reflect implementation details of Yade, they will not be compatible between different versions. Use them only for short-term saving of scenes. Python is the high-level description Yade uses.

Python attribute access¶

The macro YADE_CLASS_BASE_DOC_* macro family introduced above is (behind the scenes) also used to create functions for accessing attributes from Python. As already noted, set of serialized attributes and set of attributes accessible from Python are identical. Besides attribute access, these wrapper classes imitate also some functionality of regular python dictionaries:

Yade [20]: s=Sphere()

Yade [21]: s.radius ## read-access

Out[21]: nan

Yade [22]: s.radius=4. ## write access

Yade [23]: s.dict().keys() ## show all available keys

Out[23]: dict_keys(['radius', 'color', 'wire', 'highlight'])

Yade [24]: for k in s.dict().keys(): print(s.dict()[k]) ## iterate over keys, print their values

....:

4.0

Vector3(1,1,1)

False

False

Yade [25]: s.dict()['radius'] ## same as: 'radius' in s.keys()

Out[25]: 4.0

Yade [26]: s.dict() ## show dictionary of both attributes and values

Out[26]: {'radius': 4.0, 'color': Vector3(1,1,1), 'wire': False, 'highlight': False}

YADE_CLASS_BASE_DOC_* macro family¶

There are several macros that hide behind them the functionality of Sphinx documentation, Run-time type identification (RTTI), Attribute registration, Python attribute access, plus automatic attribute initialization and documentation. They are all defined as shorthands for the macro YADE_CLASS_BASE_DOC_ATTRS_INIT_CTOR_PY, which is itself a shorthand for the base macro YADE_CLASS_BASE_DOC_ATTRS_DEPREC_INIT_CTOR_PY with some arguments left out. They must be placed in class declaration’s body (.hpp file):

#define YADE_CLASS_BASE_DOC(klass,base,doc) \

YADE_CLASS_BASE_DOC_ATTRS(klass,base,doc,)

#define YADE_CLASS_BASE_DOC_ATTRS(klass,base,doc,attrs) \

YADE_CLASS_BASE_DOC_ATTRS_CTOR(klass,base,doc,attrs,)

#define YADE_CLASS_BASE_DOC_ATTRS_CTOR(klass,base,doc,attrs,ctor) \

YADE_CLASS_BASE_DOC_ATTRS_CTOR_PY(klass,base,doc,attrs,ctor,)

#define YADE_CLASS_BASE_DOC_ATTRS_CTOR_PY(klass,base,doc,attrs,ctor,py) \

YADE_CLASS_BASE_DOC_ATTRS_INIT_CTOR_PY(klass,base,doc,attrs,,ctor,py)

#define YADE_CLASS_BASE_DOC_ATTRS_INIT_CTOR_PY(klass,base,doc,attrs,init,ctor,py) \

YADE_CLASS_BASE_DOC_ATTRS_INIT_CTOR_PY(klass,base,doc,attrs,inits,ctor,py)

Expected parameters are indicated by macro name components separated with underscores. Their meaning is as follows:

klass(unquoted) name of this class (used for RTTI and python)

base(unquoted) name of the base class (used for RTTI and python)

docdocstring of this class, written in the ReST syntax. This docstring will appear in generated documentation (such as CpmMat). It can be as long as necessary, use string literal to avoid sequences interpreted by c++ compiler (so that some backslashes don’t have to be doubled, like in \(\sigma=\epsilon E\)) instead of writing this:

":math:`\\sigma=\\epsilon E"

Write following:

R"""(:math:`\sigma=\epsilon E`)""". When theR"""(raw text)"""is used the escaped characters\nand\tdo not have to be written. Newlines and tabs can be used instead. For example see here and here. Hyperlink the documentation abundantly withyref(all references to other classes should be hyperlinks). See previous section about syntax on using references and anchors.attrsAttribute must be written in the form of parethesized list:

((type1,attr1,initValue1,attrFlags,"Attribute 1 documentation")) ((type2,attr2,,,"Attribute 2 documentation")) // initValue and attrFlags unspecified

This will expand to

data members declaration in c++ (note that all attributes are public):

public: type1 attr1; type2 attr2;

Initializers of the default (argument-less) constructor, for attributes that have non-empty

initValue:Klass(): attr1(initValue1), attr2() { /* constructor body */ }

No initial value will be assigned for attribute of which initial value is left empty (as is for attr2 in the above example). Note that you still have to write the commas.

Registration of the attribute in the serialization system (unless disabled by attrFlags – see below)

- Registration of the attribute in python (unless disabled by attrFlags), so that it can be accessed as

klass().name1. The attribute is read-write by default, see attrFlags to change that.

This attribute will carry the docstring provided, along with knowledge of the initial value. You can add text description to the default value using the comma operator of c++ and casting the char* to (void):

((Real,dmgTau,((void)"deactivated if negative",-1),,"Characteristic time for normal viscosity. [s]"))

leading to CpmMat::dmgTau.

The attribute is registered via

boost::python::add_propertyspecifyingreturn_by_valuepolicy rather thanreturn_internal_reference, which is the default when usingdef_readwrite. The reason is that we need to honor custom converters for those values; see note in Custom converters for details.

- Registration of the attribute in python (unless disabled by attrFlags), so that it can be accessed as

Attribute flags

By default, an attribute will be serialized and will be read-write from python. There is a number of flags that can be passed as the 4th argument (empty by default) to change that:

Attr::noSaveavoids serialization of the attribute (while still keeping its accessibility from Python)

Attr::readonlymakes the attribute read-only from Python

Attr::triggerPostLoadwill trigger call topostLoadfunction to handle attribute change after its value is set from Python; this is to ensure consistency of other precomputed data which depend on this value (such asCell.trsfand such)

Attr::hiddenwill not expose the attribute to Python at all

Attr::noResizewill not permit changing size of the array from Python [not yet used]Flags can be combined as usual using bitwise disjunction

|(such asAttr::noSave | Attr::readonly), though in such case the value should be parenthesized to avoid a warning with some compilers (g++ specifically), i.e.(Attr::noSave | Attr::readonly).Currently, the flags logic handled at runtime; that means that even for attributes with

Attr::noSave, their serialization template must be defined (although it will never be used). In the future, the implementation might be template-based, avoiding this necessity.

deprecList of deprecated attribute names. The syntax is

((oldName1,newName1,"Explanation why renamed etc.")) ((oldName2,newName2,"! Explanation why removed and what to do instead."))

This will make accessing

oldName1attribute from Python return value ofnewName, but displaying warning message about the attribute name change, displaying provided explanation. This happens whether the access is read or write.If the explanation’s first character is

!(bang), the message will be displayed upon attribute access, but exception will be thrown immediately. Use this in cases where attribute is no longer meaningful or was not straightforwardsly replaced by another, but more complex adaptation of user’s script is needed. You still have to givenewName2, although its value will never be used – you can use any variable you like, but something must be given for syntax reasons).Warning

Due to compiler limitations, this feature only works if Yade is compiled with gcc >= 4.4. In the contrary case, deprecated attribute functionality is disabled, even if such attributes are declared.

initParethesized list of the form:

((attr3,value3)) ((attr4,value4))

which will be expanded to initializers in the default ctor:

Klass(): /* attributes declared with the attrs argument */ attr4(value4), attr5(value5) { /* constructor body */ }

The purpose of this argument is to make it possible to initialize constants and references (which are not declared as attributes using this macro themselves, but separately), as that cannot be done in constructor body. This argument is rarely used, though.

ctorwill be put directly into the generated constructor’s body. Mostly used for calling createIndex(); in the constructor.

Note

The code must not contain commas outside parentheses (since preprocessor uses commas to separate macro arguments). If you need complex things at construction time, create a separate init() function and call it from the constructor instead.

pywill be appended directly after generated python code that registers the class and all its attributes. You can use it to access class methods from python, for instance, to override an existing attribute with the same name etc:

.def_readonly("omega",&CpmPhys::omega,"Damage internal variable") .def_readonly("Fn",&CpmPhys::Fn,"Magnitude of normal force.")

def_readonlywill not work for custom types (such as std::vector), as it bypasses conversion registry; see Custom converters for details.

Exposing function-attributes to GUI¶

Usually to expose a more complex data a getter and setter functions are used, for example Body::mask. They are accessible from python. To make them visible in GUI without a corresponding variable at all a function virtual ::boost::python::dict pyDictCustom() const { …… }; must be overridden. For example see Interaction.hpp where a special attribute isReal is exposed to GUI. To mark such attribute as readonly an extra information has to be added to its docstring: :yattrflags:`2`. Normally it is put there by the class attribute registration macros. But since it is not a variable, such attribute has to be added manually.

Special python constructors¶

The Python wrapper automatically creates constructor that takes keyword (named) arguments corresponding to instance attributes; those attributes are set to values provided in the constructor. In some cases, more flexibility is desired (such as InteractionLoop, which takes 3 lists of functors). For such cases, you can override the function Serializable::pyHandleCustomCtorArgs, which can arbitrarily modify the new (already existing) instance. It should modify in-place arguments given to it, as they will be passed further down to the routine which sets attribute values. In such cases, you should document the constructor:

.. admonition:: Special constructor

Constructs from lists of …

which then appears in the documentation similar to InteractionLoop.

Enums¶

It is possible to expose enum class in GUI in a dropdown menu. This approach is backward compatible, an assignment of int value in an old python script will work the same as before. Additionally it will be possible to assign the string type values to an enum. To enable the dropdown menu one must #include <lib/serialization/EnumSupport.hpp> and put a macro YADE_ENUM( Scope , EnumName , (ValueName1)(ValueName2)(ValueName3)(ValueName4) ) in a .cpp file. Where each macro argument means:

Scopeis the full scope name in which the enum resides. For example the scope ofyade::OpenGLRenderer::BlinkHighlightisyade::OpenGLRenderer.

EnumNameis the name of the enum type (not variable name!) to be registered

ValueNameare all enum values that are to be exposed to python. They have to be updated if the C++ enum declaration in.hppfile changes.

After it is registered, like for example in OpenGLRenderer.cpp it is available for use. Additionally the registered enum class type definitions are exposed in yade.EnumClass_* scope, for example one can check the names and values dictionaries:

Yade [27]: yade.EnumClass_BlinkHighlight.names

Out[27]:

{'NEVER': yade.EnumClass_BlinkHighlight.NEVER,

'NORMAL': yade.EnumClass_BlinkHighlight.NORMAL,

'WEAK': yade.EnumClass_BlinkHighlight.WEAK}

Yade [28]: yade.EnumClass_BlinkHighlight.values

Out[28]:

{0: yade.EnumClass_BlinkHighlight.NEVER,

1: yade.EnumClass_BlinkHighlight.NORMAL,

2: yade.EnumClass_BlinkHighlight.WEAK}

Keep in mind that these are not the variable instances hence trying to assign something to them will not change the blinkHighlight setting in GUI. To change enum value from python the respective variable must be assigned to, such as yade.qt.Renderer().blinkHighlight. Trying to assign an incorrect value will throw an exception. For example:

Yade [29]: r = yade.NewtonIntegrator() # this is only a test of enum, not of NewtonIntegrator

Yade [30]: r.rotAlgorithm # check current rotation algorithm (also available in the GUI Inspector of Engines)

Out[30]: yade.EnumClass_RotAlgorithm.delValle2023

Yade [31]: r.rotAlgorithm = 'Omelyan1998'

Yade [32]: try:

....: r.rotAlgorithm = 20 # assigning incorrect value throws an exception

....: except:

....: print("Error, value is still equal to:",r.rotAlgorithm)

....:

Error, value is still equal to: Omelyan1998

Yade [33]: r.rotAlgorithm

Out[33]: yade.EnumClass_RotAlgorithm.Omelyan1998

Alternatively the dropdown menu in GUI can be used for the same effect.

Static attributes¶

Some classes (such as OpenGL functors) are instantiated automatically; since we want their attributes to be persistent throughout the session, they are static. To expose class with static attributes, use the YADE_CLASS_BASE_DOC_STATICATTRS macro. Attribute syntax is the same as for YADE_CLASS_BASE_DOC_ATTRS:

class SomeClass: public BaseClass{

YADE_CLASS_BASE_DOC_STATICATTRS(SomeClass,BaseClass,"Documentation of SomeClass",

((Type1,attr1,default1,"doc for attr1"))

((Type2,attr2,default2,"doc for attr2"))

);

};

additionally, you have to allocate memory for static data members in the .cpp file (otherwise, error about undefined symbol will appear when the plugin is loaded):

There is no way to expose class that has both static and non-static attributes using YADE_CLASS_BASE_* macros. You have to expose non-static attributes normally and wrap static attributes separately in the py parameter.

Returning attribute by value or by reference¶

When attribute is passed from c++ to python, it can be passed either as

value: new python object representing the original c++ object is constructed, but not bound to it; changing the python object doesn’t modify the c++ object, unless explicitly assigned back to it, where inverse conversion takes place and the c++ object is replaced.

reference: only reference to the underlying c++ object is given back to python; modifying python object will make the c++ object modified automatically.

The way of passing attributes given to YADE_CLASS_BASE_DOC_ATTRS in the attrs parameter is determined automatically in the following manner:

Vector3,Vector3i,Vector2,Vector2i,Matrix3andQuaternionobjects are passed by reference. For instance::O.bodies[0].state.pos[0]=1.33

will assign correct value to

xcomponent of position, without changing the other ones.- Yade classes (all that use

shared_ptrwhen declared in python: all classes deriving from Serializable declared withYADE_CLASS_BASE_DOC_*, and some others) are passed as references (technically speaking, they are passed by value of theshared_ptr, but by virtue of its sharedness, they appear as references). For instance:: O.engines[4].damping=.3

will change damping parameter on the original engine object, not on its copy.

- Yade classes (all that use

- All other types are passed by value. This includes, most importantly, sequence types declared in Custom converters, such as

std::vector<shared_ptr<Engine> >. For this reason, :: O.engines[4]=NewtonIntegrator()

will not work as expected; it will replace 5th element of a copy of the sequence, and this change will not propagate back to c++.

- All other types are passed by value. This includes, most importantly, sequence types declared in Custom converters, such as

Multiple dispatch¶

Multiple dispatch is generalization of virtual methods: a Dispatcher decides based on type(s) of its argument(s) which of its Functors to call. Number of arguments (currently 1 or 2) determines arity of the dispatcher (and of the functor): unary or binary. For example:

InsertionSortCollider([Bo1_Sphere_Aabb(),Bo1_Facet_Aabb()])

creates InsertionSortCollider, which internally contains Collider.boundDispatcher, a BoundDispatcher (a Dispatcher), with 2 functors; they receive Sphere or Facet instances and create Aabb. This code would look like this in c++:

shared_ptr<InsertionSortCollider> collider=(new InsertionSortCollider);

collider->boundDispatcher->add(new Bo1_Sphere_Aabb());

collider->boundDispatcher->add(new Bo1_Facet_Aabb());

There are currenly 4 predefined dispatchers (see dispatcher-names) and corresponding functor types. They are inherited from template instantiations of Dispatcher1D or Dispatcher2D (for functors, Functor1D or Functor2D). These templates themselves derive from DynlibDispatcher (for dispatchers) and FunctorWrapper (for functors).

Example: IGeomDispatcher¶

Let’s take (the most complicated perhaps) IGeomDispatcher. IGeomFunctor, which is dispatched based on types of 2 Shape instances (a Functor), takes a number of arguments and returns bool. The functor “call” is always provided by its overridden Functor::go method; it always receives the dispatched instances as first argument(s) (2 × const shared_ptr<Shape>&) and a number of other arguments it needs:

class IGeomFunctor: public Functor2D<

bool, //return type

TYPELIST_7(const shared_ptr<Shape>&, // 1st class for dispatch

const shared_ptr<Shape>&, // 2nd class for dispatch

const State&, // other arguments passed to ::go

const State&, // …

const Vector3r&, // …

const bool&, // …